Pain Profile: Snapping Scapula

Snapping Scapula Syndrome is characterised by a loud cracking or popping sound when the scapula moves over the thoracic rib cage, most commonly with overhead movements. This cracking sound can be present with or without pain. Snapping Scapula Syndrome also goes by the name “Scapulothoracic Crepitis”. It is a fairly common condition that is greatly under diagnosed.

To understand more about this condition, we must first understand the structures and function of the Scapulothoracic Joint.

Anatomy of the Scapulothoracic Joint

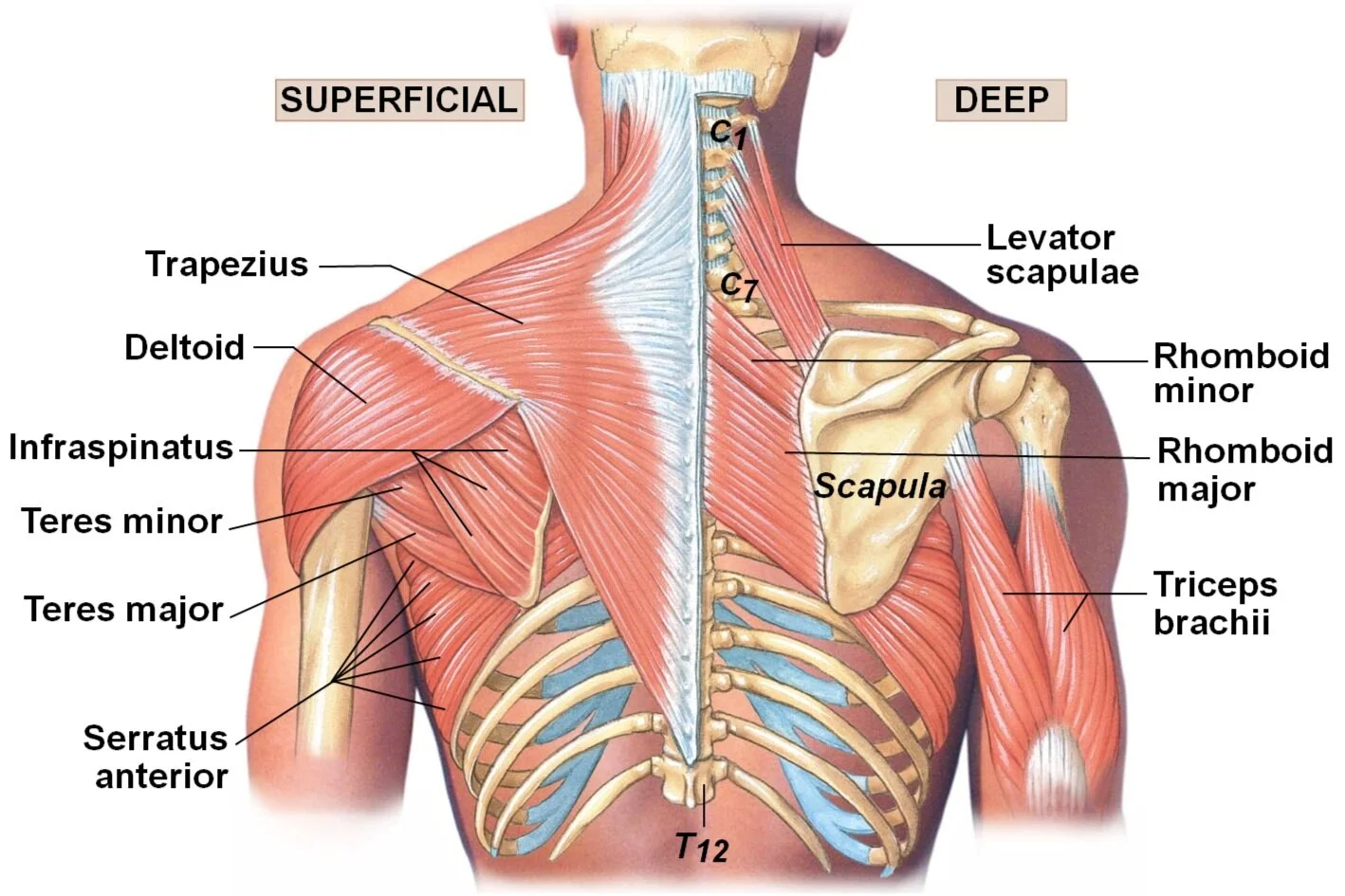

The Scapulothoracic joint consists of the scapula (shoulder blade) and the posterior surface of the thoracic rib cage, normally over ribs 2 to 7. It isn't like most of the other joints around the shoulder in that it doesn't have a capsule. There is no cartilage or synovial fluid. What it does have is a group of muscle and bursa that normally allow for a smooth, gliding motion of the two bony surfaces. It is when this movement is disrupted that issues can arise.

There are 17 muscles that attach to the scapula with the vast majority of them playing a role in these movements. Altered movement patterns of the scapula are referred to as “Scapular Dyskinesis”.

Causes of Snapping Scapula Syndrome

There is no one singular cause for the development of Snapping Scapula Syndrome. This is why diagnosis of the cause is important when it comes to how we progress with treatment, rehabilitation and/or referral. Snapping scapula occurs when there is a disruption of the normal movement and function of the scapula over the thoracic rib cage. Smooth movement of this joint relies on the underlying muscles and bursa of the area.

History of overuse – years of repetitive movements can lead to wear patterns in the bony or soft tissues structures. One of the noted movements which can lead to aggravation of this condition is a history of overhead movements.

Muscular atrophy – atrophy is when your muscles become smaller and weaker through incorrect or under use. Some specific muscles involved here include the serratus anterior and the subscapularis. Both muscles are positioned between the scapula and the rib cage which, when healthy, can create a buffer between the two bony surfaces. Weakness of these muscles can also lead to scapular winging. Under use of muscles can be related to long hours in stationary “work/desk” postures.

Altered posture – a common posture for those presenting with this condition is that of a moderate to severe forward position head with anteriorly rounded shoulders. Increased thoracic kyphosis (hunchback) and abducted forward-tipped scapular can also be involved. Tightness of the pectoralis minor muscle can also alter the starting position of the scapula.

Previous injury or surgery – anything that may have led to change in function or structure must be considered.

Rare or uncommon causes include;

osteochondromas

benign tumour

bone spurs

scapular or rib fractures

nerve injuries

Signs and Symptoms of Snapping Scapula

Patients who experience Snapping Scapula will commonly present with a crunching or cracking sound with movement of the shoulder blade. This can be present with or without pain during movement. If one of the bursa between the shoulder blade and thoracic rib cage becomes inflamed, you may have a dull ache pain at rest.

Differential diagnosis - What else could it be?

The snapping noise could be coming from the long head of biceps as it can slip out of the groove that it runs through creating a clicking noise. A labral tear of the shoulder can also lead to clicking noise through movement.

Pain around the medial border of the scapula could be caused by referred pain from the neck or shoulder. The image to the right shows the referral patterns for pain coming from the different levels of the neck. As you can see, pain around the medial border of the scapula can be referred from spinal levels C5 through C8.

Treatment of Snapping Scapula

As with most physical complaints, conservative (non-operative) treatment is the preferred option. This is the front-line approach to recovery if it is believed that the cause of the crepitus is from altered posture, soft tissue abnormalities, scapular winging or scapulothoracic dyskinesis. For all other causes, further investigation may be required.

Reduce inflammation - if there is inflammation of the bursa and you are safe to do so, a short course of NSAIDs may be helpful in reducing pain and inflammation in the early stages. An anti-inflammatory injection into the bursa may also be considered depending on severity of inflammation. Reducing inflammation can make rehabilitation easier and decrease flair-ups.

Manual therapy – soft tissue techniques, mobilisations and passive stretching focusing on the functionally tightened and/or inhibited and weak muscles can be effective in increasing active range of movement and decreasing symptomatic pain.

Strengthening program – with the primary role of the scapular muscles being stability and providing static posturing of the shoulder girdle, endurance training should be emphasised. These muscles need to work for long periods of time. Rehabilitation will begin with static exercises with a gradual progression into functional movements that mimic actions undertaken regularly by the patient.

Postural retraining – part of the rehabilitation program will train proper postural alignment. This will allow for maximal neuromuscular efficiency and normal length-tension relationships amongst muscle groups during functional movement patterns. The areas focused on during postural retraining will include head and neck positioning, thoracic kyphosis and scapular positioning.

Resources:

Manske, R., Reiman, M., & Stovak, M. (2004). Nonoperative and Operative Management of Snapping Scapula. The American Journal Of Sports Medicine, 32(6), 1554-1565. doi: 10.1177/0363546504268790

Osias, W., Matcuk, G., Skalski, M., Patel, D., Schein, A., Hatch, G., & White, E. (2017). Scapulothoracic pathology: review of anatomy, pathophysiology, imaging findings, and an approach to management. Skeletal Radiology, 47(2), 161-171. doi: 10.1007/s00256-017-2791-6